The Pattern of Hinduism and Hindu Temple Building in the U.S.

BY: KAREN PECHILIS PRETISS

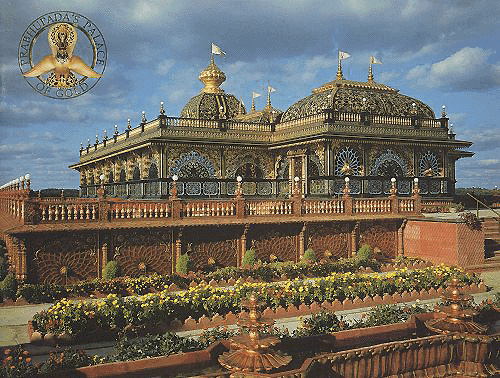

Srila Prabhupada's Palace of Gold, West Virginia

Nov 22, USA (SUN) — Hinduism has become increasingly established in the U.S. through a series of encounters over the past 150 years. These encounters are emblematic of Americans' increasing familiarity with Indian, and Asian, traditions; of contact between Americans and Indian immigrants, and of relationships among cultural traditions in a society that is self-consciously pluralistic. Two distinct forms of Hinduism have contributed to these encounters. In recent public lectures, Professor Vasudha Narayanan of the University of Florida has classified Hindu institutions in America today into two categories from Hindu tradition: 1. organizations that promote self-help practices (e.g. yoga, meditation), and 2. organizations that provide the means for formal ritual worship (e.g. temples). (See also her website on the Pluralism Project Affiliates page.)

In Hindu Indian tradition, the paths of self-help and ritual worship are co-existing classical paradigms and present-day realities. The path of self-help is traditionally realized in the intense relationship between the guru and disciple; the path of ritual worship is traditionally realized in liturgical activities in temples performed by priests on behalf of worshipers.

These are not mutually exclusive ways of worship; for example, there is often a temple at a guru's ashram, and temple priests have personal client relationships with worshipers. Today, these streams co-exist in America, as they do in India. However, the historical establishment of Hinduism in America reveals a distinctive pattern: For the first hundred years of Hinduism in the U.S., its followers have mainly practiced the self-help approach; during the last 30 years, building Hindu temples in the U.S. has become a dominant focus. This pattern is more controversially characterized as Americans representing Hinduism in America on their own terms during the initial period, followed by Hindu Indians representing Hinduism in America on their own terms in recent years.

The Self-Help Approach: Examples and Issues

The engagement of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau with the famous Hindu text, the Bhagavad Gita (via Charles Wilkins' 1785 translation), represents a notable early American encounter with Hindu ideals. Both authors viewed the Gita as an important Asian contribution to the consideration of familiar philosophical issues, especially the nature of self-discipline. As members of the literati, Emerson and Thoreau approached the Gita through self-study and reflection: Emerson wrote of his reactions to the text in his letters and journals, and Thoreau brought the text on his pilgrimage along the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. In their writings, knowledge of Asian tradition is an intellectual and spiritual pilgrimage.

Instruction in the nature of Hindu ideals by a Hindu representative came some 40 years later, in the very public forum of the 1893 World's Parliament of Religions in Chicago. Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902), a disciple of Ramakrishna, authoritatively presented the Hindu worldview to an appreciative crowd. Sincerely-and shrewdly-he emphasized the worldview according to Advaita Vedanta philosophy, which posits a non-duality between the divine and the essence of humanity. Thus, Vivekananda eschewed the "idolatry" of some forms of Hinduism as "the attempt of undeveloped minds to grasp higher spiritual truths," in favor of an image of Hinduism as a process of spiritual development: "The Hindu religion does not consist in struggles and attempts to believe a certain doctrine or dogma, but in realizing; not in believing, but in being and becoming." The personal spiritual quest of Emerson and Thoreau was thus affirmed, yet Vivekananda placed this quest squarely within the context of the authority of Hindu tradition and the authority of a Hindu teacher. Further, Vivekananda appealed to this image of process in his assertion that all religions were one: "To the Hindu, then, the whole world of religions is only a traveling, a coming up, of different men and women, through various conditions and circumstances, to the same goal.

Every religion is only an evolving of God out of the material man; and the same God is the inspirer of all of them. Why, then, are there so many contradictions? They are only apparent, says the Hindu. The contradictions come from the same truth adapting itself to the different circumstances of different natures. It is the same light coming through different colors." It was his assertion of the unity among religions that forged a rapprochement between speaker and audience, and Hinduism and Americans.

Vivekananda also hoped that the Americans' encounter with Hinduism would lead to active engagement: One year after the World's Parliament, he established the Vedanta Society in New York, "the first Hindu organization designed to attract American adherents." Other teachers from India also sought to establish early institutions in America for the teaching of Hinduism. Baba Premanand Bharati was a Bengali disciple of Caitanya who lectured in the U.S. for five years and established the Krishna Samaj at the turn of the century. Swami Paramananda spent two years as an assistant at the New York Vedanta Society before establishing his own Vedanta societies in the Boston and Los Angeles areas; in 1923 he founded Ananda Ashrama, a mountain retreat in southern California.

Swami Paramahansa Yogananda came to America in 1920 as a delegate to the International Congress of Religious Liberals held in Boston, then settled in America and founded the Yogoda-Satsang (Self-Realization Fellowship). His methodology involved the "science" of Kriya Yoga, which is the "union (yoga) with the Infinite through a certain action or rite (kriya)." Although he published several books on his vision of spiritual path, including the enormously popular Autobiography of a Yogi (1946), Yogananda maintained that a direct relationship with a guru was the key: "Because of certain yogic injunctions, I cannot give a full explanation of Kriya Yoga in the pages of a book intended for the general public. The actual technique must be learned from a Kriyaban or Kriya Yogi; here a broad reference must suffice." The path of self-help, understood both traditionally and by these early Hindu teachers in America, is for a disciple to work toward spiritual liberation through a combination of practice on one's own and instruction from the guru.

Hindu Temples in America

The Vedanta Society is credited with building the first Hindu temple in the U.S., in San Francisco in 1906; others followed, such as the Hollywood Temple in 1938, and the Santa Barbara Temple in 1956 (website: www.vedanta.org). In keeping with the image of Hinduism Vivekananda had presented to Americans, the focus in these temples tended to be on understanding scripture. The phenomenon of building temples with a focus on the ritual worship of images began in the 1970s and was directly related to the presence of Hindu Indian immigrants in America. In 1965 the Immigration Act liberated the long-frozen immigration of Asians to America by removing the national origins quota system. In addition, the Act's "family reunification" policy facilitated a second wave of Asian immigration. The Hindu temples built in the U.S. during the 1970s can be classified into two categories. One, as ISKCON temples: These temples were built for a specific devotional community, which included both Euro-Americans and Indian-Americans. Two, as Hindu immigrant temples built for the Hindu immigrant community, which tend to incorporate diverse ways of worship as they attempt to bring Hindus together as a cultural community.

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (1896-1977), the founder of ISKCON (the International Society for Krishna Consciousness), came to New York City in 1965. Within one year, Prabhupada had established a "storefront ashram" at 26 Second Avenue, where he would give lectures on the Gita every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday from 7:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. At those sessions, he would teach young American seekers about bhakti, based upon the teachings of a classical Hindu saint, Chaitanya (1486-1533). Bhakti, a Sanskrit word whose root meanings are sharing, participation, and devotion, is a religious path defined by three interrelated premises: That humankind shares in the nature of divinity; that humankind must participate in the worship of divinity through action--especially chanting God's name; and that humankind must be guided by devotion to God and to a spiritual guru. There is much that can, and has, been written about ISKCON. For the purposes of this essay, we will note that Prabhupada's vision included both the guru-disciple relationship and temple worship. Thus, it combined the personal spiritual quest, embodied by the guru, with traditions of ritual worship. ISKCON built temples in cities across America, with the most famous being the elaborate Palace of Gold in New Vrindaban, West Virginia (website: www.palaceofgold.com ).

In north-central New Jersey, there is an ISKCON temple at 100 Jacksonville Road in Towaco (near Parsippany). The temple is a large colonial-style house, set on a hill off a winding country road. The disciples there say that the house has belonged to ISKCON for twenty years. The house is surrounded by a beautiful garden which is tended by disciples. In total, the temple possesses some two and a half acres of land which, according to devotees, makes it liable for taxes, since it falls below the five acre minimum the town requires to bestow tax-free status on religious organizations. Several members live in the house; it is also a gathering place for ISKCON members in this and surrounding areas. There is a wide, open porch that greets one at the top of the stairs up the hill, and indeed the disciples are warm and friendly, in the context of encouraging others to take up the path of bhakti according to ISKCON.

The worship area is a spacious room off the entrance foyer. At the front of the room there is a large altar, rather like a stage, that holds the holy images. These are presented in traditional style, situated in niches covered by carved wooden canopies and dressed in colorful Indian textiles. All of the images are specifically related to the worship of Krishna as understood by Prabhupada, and include the historical leaders Sri Krishna Chaitanya and Sri Niyananda (Sri Sri Gaura Nitai), and forms of Krishna-Vishnu (Jagannatha, Baladev and Subhadra, and Narasimha). There are also smaller, metal images of the two leaders; it is these images that are bathed and "put to bed" in the evening ritual.

Although the temple is open all week, Sunday is a special day, since it is a time when many disciples-up to two or three hundred-can gather. The majority the disciples are north Indians, although there are some Euro-American disciples, some wearing traditional Indian dress. The program starts around 5:00 p.m., and includes group chanting of the Hare Krishna mantra and the singing of devotional songs, traditional worship of the images (called puja, 'honor', or arati), and a spiritual talk. The worship is followed by the taking of prasad, which is vegetarian food offered to and then blessed by God; in this case the meaning is extended to include a communal dinner for the disciples. The disciples perform all service relating to the temple; however, performing the puja and cooking the meal are special services for which there are standards a disciple must meet in order to be eligible for their performance. For this service, a disciple must have been initiated into ISKCON, and must chant mantras a minimum number of four times per day.

Upon occasion, a formal speaker will come to the service to lead the community and deliver a spiritual talk. These speakers are from the GBC, the Governing Body Commission of ISKCON, a group of twelve leaders originally established by Prabhupada but reformulated during the crisis of leadership in the late 1970s and 80s. GBC members are orange-robed sannyasins (spiritual leaders who have taken a vow of celibacy) who are responsible for providing leadership to ISKCON members within defined geographical areas. Their periodic visits to ISKCON temples provide spiritual guidance for group members and link them to the worldwide community of ISKCON, which underscores the movement's emphasis on communal worship and spirituality.

In contrast, priestly temples in India do not traditionally operate in a congregational mode; the daily puja ceremonies held at temples attract many worshipers, but they do not necessarily embrace structures, such as communal chanting, that promote a sense of congregational unison. Two such temples in the U.S. were dedicated in 1977, the Maha Vallabha Ganapati Devasthanam in Flushing, New York (commonly referred to as "The Ganesha Temple", whose website, has a section on "Temples Online" with links to other temples), and the Sri Venkateswara Temple in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (website: www.svtemple.org ). As distinct from their Indian counterparts, these temples do attempt to foster a sense of community among Hindus, although, as distinct from ISKCON, they tend to do so along ethnic and cultural lines.

Pilgrimage is an apt lens through which to understand the nature of Hindu priestly temples in the U.S., as I suggested in a paper I delivered at a panel chaired by Dr. Diana Eck at the American Academy of Religion annual meeting in 1991. In that paper, I presented research I had done on the Hindu Temple of Greater Chicago in Lemont, Illinois (website: www.ramatemple.org ). Pilgrimage, as analyzed by Victor Turner, encourages participation across sectarian lines, which are de-emphasized in favor of a shared experience. Both the Flushing and Pittsburgh temples are dedicated to gods that are worshiped across traditional Hindu sectarian lines: Ganesha is the elephant-faced god who is known as the remover of obstacles, and Venkateswara is a powerful form of Vishnu who has a major pilgrimage site (it is called "the richest temple in India") in Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh. The Flushing temple is unusual in the lengths it goes to promote a sense of a shared experience: All the major deities are represented equally in the temple, supported by a graphic image of the unity of religions at the center, which is a lotus image with the symbols of Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity, Judaism, and Islam in its petals. More common is the strategy of the Venkateswara Temple, in which a popular god is chosen as the main deity, with other deities represented in subordinate satellite shrines within the complex.

A well-known Venkateswara Temple in New Jersey is the Hindu Temple and Cultural Society of USA Inc., Sri Venkateswara Temple (Balaji Mandir) and Community Center at 780 Old Farm Road in Bridgewater, New Jersey, 08807 (phone 908-725-4477. This temple seeks to serve all members of the surrounding area who are Hindu, although the majority of people involved in its creation are south Indian, and as an institution it is south Indian in appearance and tends to follow the south Indian festival calendar. As with many suburban Hindu temples, the momentum for the Bridgewater Temple developed during the 1980s, relating to several factors: 1. a critical mass of Hindu Indians had settled in the surrounding area, especially in Edison, New Jersey; 2. Members of the Hindu Indian community, most of whom are employed in the professional sector, had savings to contribute and the ability to participate in fundraising activities for the expensive project of building a temple; and 3. There was a growing concern among parents in the community that their children would lose touch with traditional Hindu institutions and values. This central New Jersey group took a first step by purchasing a nearly three acre plot of land in Bridgewater, New Jersey, on a quiet lane just off of a major north-south roadway, Route 202/206.

Through the 1980s, worship and cultural activities were held in a modestly-sized brick building. This was considered a temporary structure which would be replaced as soon as funds had been gathered for a traditional-style temple. The images inside the temple reflected this perspective: They were all metal festival (utsava) images, which are designed to be processed outside of the temple sanctum on festival occasions. Since they are moveable, they are not considered permanent images as required in a traditional Hindu temple. Within these limitations, the temple room within the building was beautifully arranged and the rituals therein were performed in the correct traditional style by priests who were brought over from India specifically for that purpose. Then as now, the priests tend to be from south India, especially the states of Andhra Pradesh and Tamilnadu, in keeping with the identity of the majority of worshipers at the temple. However, the priests speak a variety of Indian languages, including those of north India, so that they can serve all worshipers. This building continues to be used for festivals, such as the Gita Jayanti recitation of the Bhagavad Gita each December and it is especially popular for weddings.

In the late 1980s, momentum increased for the building of a large, traditional style temple on a small hill adjacent to the brick building. Into the early 1990s, a series of fundraising activities were held, including a drive for devotees to 'purchase' a brick that would be used in the temple's foundation (donation $150.00 per brick). Work was started for construction of the temple in the mid 1990s. It involved elaborate ritual preparation of the land on the building site, because in the traditional ideology a Hindu temple is not constructed on top of the earth but instead rises up organically out of the earth. Many specialists were brought over from India for the correct performance of these rituals. When the basic structure was completed, and the enormous stone images of the gods had been brought over from India and installed, the Temple held a Mahakumbhabhishekam ceremony to inaugurate the opening of the temple for formal worship. This festival was celebrated on June 12-14, 1998, with several thousand devotees in attendance. Work continues on the ornamentation of the temple so that it will look just like the traditional stone temples in south India, including features such as: a golden tower above the main sanctum, a huge tower decorated with images above the main entrance to the temple, decorative niches (in this case surrounding windows) and pillars.

Inside the temple (photographs are not allowed), there is the main shrine with a twelve-foot high

image of Venkateswara, surrounded by smaller shrines to other popular deities (e.g. Shiva, Durga, Krishna, Rama). As the worshipers walk around the temple, pausing before and then circumambulating these shrines to pay their respects to the deities, the effect is one of pilgrimage.

New Hindu temples continue to be established in suburban New Jersey as well. An example is the Durga Mandir at 4240 Route 27, South Brunswick, New Jersey.

This temple celebrates the Goddess, who is portrayed in classical mythology as a supreme being and dispeller of ignorance. It is less common to dedicate an independent temple to the Goddess, but it is a traditional mode within Hindu worship. Worshipers gather at the Durga Mandir on Sunday afternoons for devotional activities, including a puja performed by devotees to a painting of the Goddess, the recitation of a scriptural text (e.g. the Ramayana) by a small group of the worshipers on behalf of the group, and the singing of devotional songs (bhajans) by the entire group. Recently, this emerging community in service to the Goddess, which claims 1,200 members, has expanded its activities beyond its weekly gathering to the study of texts in a variety of formats, including a week-long session with an orator (Acharya Akhil Ji on the Shrimad Bhagwat Katha), and a monthly Bhagavad Gita study group.

These examples of Hindu religious communities in New Jersey, set in historical and demographic context, reveal that Hinduism is represented in diverse ways in the United States today. Both the Towaco ISKCON group and the Durga Mandir group tend towards the self-help model of worship, with puja performed by the devotees, the promotion of community worship activities performed together, and the study of scriptural texts. In the context of these similarities, the ISKCON group is oriented around a guru and a guru lineage, while the Durga Mandir has the nature of a devotional study group. In the priestly tradition, the Bridgewater Temple has successfully attempted to reproduce classical Hindu liturgical structures and practices. Although Hindus generally present Hinduism as "a way of life" instead of a "religion," the groups profiled here share an institutional basis in that they have each established a temple-more or less in the classical style-dedicated to their activities. Having a "home" such as a temple enables a group to have a foundation for its self-development as well as a platform for representing itself to others. In both directions, temples provide an enormous opportunity for teaching about Hinduism in America in ways that were not necessarily developed in or deemed appropriate to the Indian context, for example:

1. allowing people to ask constructive questions about their tradition, and thus develop new ways of thinking about it;

2. providing clear explanations of practices, beliefs, and traditions, often directed towards young people in special youth programs but also present in adult programs (study groups, language classes) and even in handouts at festivities such as weddings;

3. applying Hindu ideals to the American context, to understand that while the problems encountered here may be American, solutions can be developed consistent with Hindu values;

4. extending the teaching to a dialogue with other faith groups, either in formal interfaith dialogues or in exchange visits to each group's house of worship.

Through their public representations, Hindu temples in northern and central suburban New Jersey engage both classical Indian traditions and aspects of the American context.

Selected Sources:

Lessinger, Johanna. From the Ganges to the Hudson: Indian Immigrants in New York City. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1995.

Miller, Barbara Stoler. The Bhagavad-Gita. New York: Bantam Books, 1986. (See the Afterword, "Why Did Henry David Thoreau Take the Bhagavad-Gita to Walden Pond?")

Sharpe, Eric J. "Some Western Interpretations of the Bhagavad Gita, 1785-1885," in Peter Slater and Donald Wiebe, eds., Traditions in Contact and Change. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1983, pp. 65-86.

Tweed, Thomas A. and Stephen Prothero. Asian Religions in America: A Documentary History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Williams, Raymond Brady, ed. A Sacred Thread: Modern Transmission of Hindu Traditions in India and Abroad. Chambersberg, PA: Anima Publications, 1992.