|

|

|

|

The Mughal Influence on Vaisnavism BY: SUN STAFF

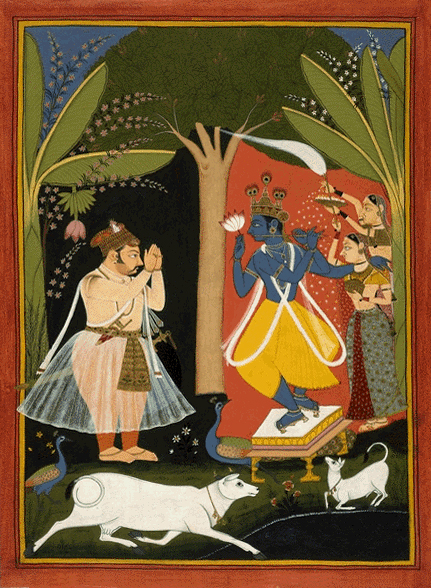

Krishna kills Shrigala Apr 06, CANADA (SUN) — A serial presentation of the Mughal effect on Vaisnava society. Today we are introducing a new Feature series that will run periodically over the next several months, alternating with segments of the Corporate ISKCON and Prasadam series, the latter soon to be launched. The Mughal influence on Vaisnavism travels the length and breadth of India, and spans several centuries. Many devotees are likely more familiar with the Mughal 'footprint' then they realize, because the Krsna theme was absorbed into much of the Mughal art and literature. The Mughal influence is seen in Vaisnava devotional paintings, temple carvings, and other iconographic and artistic expressions. Srila Prabhupada's many interesting comments on the Mughal influence will help guide our exploration of the subject.

We will focus primarily on the Modern India era, from the 16th to 18th Centuries, beginning in Lord Caitanya's Bengal, and traveling through Orissa to the south. In fact, much of South Asia's history was dominated by the Mughal influence during this period, as evidenced by historical Bengali, Hindu and Tamil texts, as well as Persian and European writings. In the Vaisnava realm, the Mughal influence is perhaps most obvious in art and literature, and in temple records from various regional areas. The Mughal polity made its mark across the political culture in administrative institutions, including the administration of Vaisnava temples. While there are many instances where the Mughals ruled Vaisnava temples quite benignly, they also destroyed many of our temples. This was particularly the case under the cruel hand of Aurangzeb the Persian (1618-1707, who made a mission of forcing the residents of India into Islamic conversion. Srila Prabhupada comments in his purport to Srimad Bhagavatam 10.1.67: "We have seen in the history of India that Aurangzeb killed his brother and nephews and imprisoned his father to fulfill political ambitions. There have been many similar instances, and Kamsa was the same type of king. Kamsa did not hesitate to kill his nephews and imprison his sister and his father. For demons to do such things is not astonishing." At the same time, Srila Prabhupada has described the Mughal influence in a somewhat positive light, particularly with respect to their ability to manage – an area in which Hindu India was not known for excelling. In the segments to come we'll explore the Rajput culture, a primary Kshatriya line that gained prominence in the 9th century. During the Mughal era, an alliance was formed between the Rajputs and the Mughals, with the Rajputs becoming officers and administrators for the Mughal empire. This historical period can also be traced through devotional paintings of the day.

A Rajput king worshipping Krishna We'll consider the Brajbhasha literature, which originated in the Vaishnava society of Vraja and Mathura, influenced by both the Mughal and Rajput courts, while the Mughals were based in Agra. This marriage of Vaisnava philosophy and Mughal custom is traceable through the Court arts of the 17th and 18th centuries in Bishnupur and Mewar, with many beautiful Krsna themes emerging. The devotees are very familiar with the interface between the Mughal Empire and the Vaisnavas in 16th century Bengal, as described in the Caitanya-caritamrta. Lord Caitanya had many interactions with the Muslims, including His famous pastime with the Chand Kazi. What is generally less well known is the history of the Mughal's arrival in Bengal, and how the domino effect of their influence caused a dramatic change in the face of India's religious history. Yet amidst a growing sea of Muslim worshippers, the Vaisnavas held fast to the school of Bhakti, keeping devotion for Sri Krsna Caitanya ever vibrant. In a book entitled The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760 by Richard M. Eaton (UC Press, 1993), which we will periodically quote throughout this series, we read the following: "Sometime in 1243–44, residents of Lakhnauti, a city in northwestern Bengal, told a visiting historian [Maulana Minhaj] of the dramatic events that had taken place there forty years earlier. At that time, the visitor was informed, a band of several hundred Turkish cavalry had ridden swiftly down the Gangetic Plain in the direction of the Bengal delta. Led by a daring officer named Muhammad Bakhtiyar, the men overran venerable Buddhist monasteries in neighboring Bihar before turning their attention to the northwestern portion of the delta, then ruled by a mild and generous Hindu monarch. Disguising themselves as horse dealers, Bakhtiyar and his men slipped into the royal city of Nudiya. Once inside, they rode straight to the king's palace, where they confronted the guards with brandished weapons. Utterly overwhelmed, for he had just sat down to dine, the Hindu monarch hastily departed through a back door and fled with many of his retainers to the forested hinterland of eastern Bengal, abandoning his kingdom altogether. This coup d'état inaugurated an era, lasting over five centuries, during which most of Bengal was dominated by rulers professing the Islamic faith. In itself this was not exceptional, since from about this time until the eighteenth century, Muslim sovereigns ruled over most of the Indian subcontinent. What was exceptional, however, was that among India's interior provinces only in Bengal—a region approximately the size of England and Scotland combined—did a majority of the indigenous population adopt the religion of the ruling class, Islam. This outcome proved to be as fateful as it is striking, for in 1947 British India was divided into two independent states, India and Pakistan, on the basis of the distribution of Muslims. In Bengal, those areas with a Muslim majority would form the eastern wing of Pakistan—since 1971, Bangladesh—whereas those parts of the province with a Muslim minority became the state of West Bengal within the Republic of India. In 1984 about 93 million of the 152 million Bengalis in Bangladesh and West Bengal were Muslims, and of the estimated 96.5 million people inhabiting Bangladesh, 81 million, or 83 percent, were Muslims; in fact, Bengalis today comprise the second largest Muslim ethnic population in the world, after the Arabs." The story of how the Vaisnavas have maintained and proliferated the supremacy of Sri Krsna and the cult of Bhakti, even in the midst of this overwhelming Mughal influence, is the story we will endeavor to tell over the course of this series.

Srila Haridas Thakur And trained in youth in Muslim creed Thy noble heart to Vaishnava truth did pass Thy holy acts thy candor plead! Is there a soul that cannot learn from thee That man must give up sect for God That thoughts of race and sect can never agree With what they call Religion broad Thy love of God and brother soul alone Bereft thyself of early friends Thy softer feelings oft to kindness prone Led on thyself for higher ends! I weep to read that Kazis and their men Persecuted thee, alas! But thou didst nobly pray for the wicked then! For thou wert Vaishnava Haridas!" (Excerpt from 'Thakur Haridas' by Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur)

| |