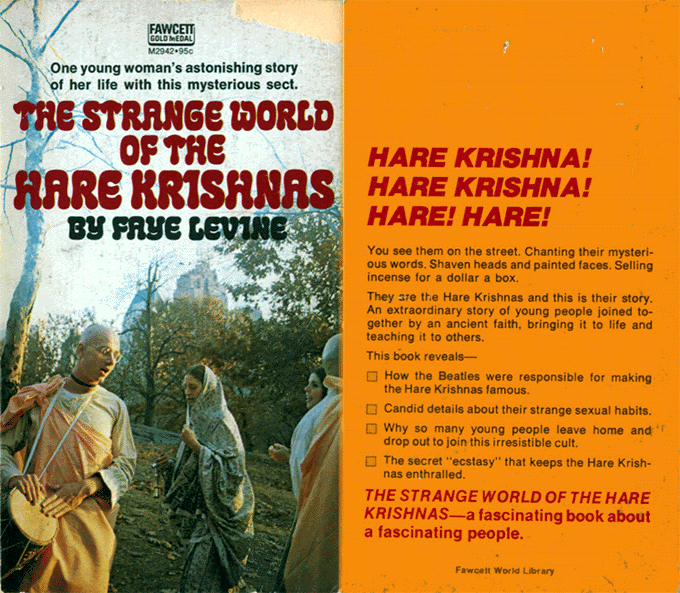

Dec 22, 2017 — NEW YORK (SUN) — An excerpt from "The Strange World Of The Hare Krishnas".

This is for all the aspiring Vaisnavas who call Radha Govinda Mandira in Brooklyn their spiritual home, the congregation their spiritual family, Srila Prabhupada their spiritual father and grandfather, and the Deities their worshipful Deities. I felt it appropriate at this time, while everyone is awaiting the outcome regarding the current situation, to share some pastimes from an earlier incarnation of Radha Govinda Mandira of Brooklyn and Manhattan.

A young lady, Faye Levine, spent a little more than a month as a resident of the Brooklyn Radha Krishna temple on Henry Street in the early 1970's. Her purpose was to write a book of her experiences among the Hare Krishnas. Although she would be considered a neophyte and an outsider, still she was accepted by the devotees and allowed to immerse herself in the process and practice of sadhana bhakti or Krsna consciousness.

The following is an excerpt from her book - The Strange World of the Hare Krishnas – describing the devotional activities during the Christmas season of 1972 when she lived at 439 Henry Street in Brooklyn with the Hare Krishnas.

Background

"In the summer of 1970, the New York Hare Krishna temple moved to a lower-middle-class Italian neighborhood, Cobble Hill, near Red Hook, about a mile from Brooklyn's business center towards the docks and warehouses. The structure, formerly a Sisters of Charity convent, stands two hundred yards down Henry Street from The Warlock Shop, said to be a center for witchcraft in New York City.

Difficulties with the neighborhood erupted in early 1971, when a local parish priest denounced the Krishna devotees as "devil worshipers." After that, local kids began taunting the devotees, and there were incidents of assault on the temple. A car was burned, windows were broken, and firecrackers were tossed into the garden. A group of hippies from Manhattan bragged about stealing books and money from ISKCON.

In response, the temple president assigned male devotees special tours of night watch in the temple and at the nearby press, where they carried iron pipes to use against intruders.

During a month at Christmas time 1972, I saw no incidents of any kind. Neighborhood people seemed friendly. Schoolchildren often as not said "Hare Krishna" when they passed devotees in the street. And when some devotees were stranded in the nearby Bergen Street subway station without cash, the first two people they asked obligingly handed over enough change for seven or eight fares.

Financial officers of the New York temple - president Bali Mardan, CPA Atreya Rishi, treasurer Kirtiraj - are trying to purchase a midtown Manhattan building...

At ISKCON Press in New York, 500,000 issues of the movement magazine are published each month. More than twenty books about Krishna Consciousness have been printed, with the Bhagavad-gita (New York: Macmillan paperback, 1972) a best-seller. In the largest and most active ISKCON center, the New York temple, 120 devotees grossed $30,000 in street earnings in one recent winter month.

Prabhupada, who now spends most of his time in India and Los Angeles, has his eye on further expansion. "We will build a World Center for ISKCON in Manhattan," he wrote recently, "among the skyscrapers, where people pass by every day, and it will be like a beacon."

A Chant for the Iron Age

The beginning of the Christmas season. Standing in a light fall of icy sleet, a band of boys and girls wearing winter jackets and mufflers over cotton Indian clothes are posted between the Empire State Building and Macy's - chanting "Hare Krishna."

Their insistent melody is accompanied by bells and drums. Some passers-by pause. They gape at the painting of a six-armed blue man the kids are holding aloft.

"Who's that supposed to be?" asks an old, seedy-looking woman.

"That's Krishna," a devotee replies, smiling.

The woman scowls. Then she spits at the feet of the dancers.

But they are imperturbable. They often encounter unfriendly receptions. The Hare Krishna missionaries see this unfriendliness not as a matter of individual inclination or character, but as a part of the larger workings of history that find us now in an Iron Age: an epoch of meanness, depravity, and increasing evil.

They believe that in ages past men lived ten thousand years and more in a single lifetime. So there was time for yoga, time to master the difficult techniques of breath control, gymnastics, and meditation. But that was the Golden Age, the Satya-yuga, before the pyramids were mystically raised, before Moses.

Our present age, which still has 427,000 years to run, is called the Kali-yuga, or Iron Age, a time of discord, short memory, and early death. We cannot be expected to master the old yoga, nor even to follow the rudiments of religion, for religion is three-quarters dead in our time and approaching extinction. The demonic is born in every man, it is taught. At the end of the present age there will be a great devastation - like Noah's flood and other even earlier catastrophes - and Krishna will appear in an incarnation named Kalki, on a horse, to slay the evildoers and bring these slain ones salvation.

The Hare Krishnas' apocalypse is rather far off, but the downward trend is irreversible. Sadly, they say, the only resource we have left is the virtually endless chanting of "Hare Krishna." So they spend their time chanting and trying to get others to chant, in the hope of making a dent in the Kali-yuga. They are on the street to communicate this imperative, to save the soul of every passer-by even if he does not understand what is happening. "Chant the holy name!" ("Haribol!") is their message.

As the Bible teaches, they keep the name of God on their tongues as they rise up, as they lie down, as they walk by the way. The devotees mainly chant the mahamantra, or great spell: Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. This is a Sanskrit formula deriving from the Indian holy books called Vedas. It might be translated as a reference to the dual (female and male) nature of God. But its power is rather said to lie in the sound vibration itself, and thus the word does not need translation.

Though they repeat this and other sacred formulas (mantras) for hours on end, the devotees do not consider such occupation a waste of time. For them, the outsider has no sense of real time, caught as he is in the illusory and temporal modes of the material realm. As the New Testament teaches, they mean to lay up treasure for themselves in heaven, which they call "the spiritual sky" and intend to enter before death.

The Vedas, the sacred literature where all the mantras are found, is older than the Old Testament. And the language of the Vedas, Sanskrit, is thought to express the most highly refined sensibility ever known to man. (The spelling of Krsna suggests the sound of the Sanskrit word and is conventionally used in rendering the great spell.)

It is written in the Vedas that before creating our universe, Lord Brahma performed one thousand years of sacrificial austerities, or chanting, and was granted a vision of the Supreme Lord. Chanting preceded creation ("in the beginning was the word") and enabled the Creator to do his work.

With this in mind, a handful of Hindu neophytes stand out in the cold New York City winter to sing and chant tirelessly in Sanskrit. In the night air and bustle of Herald Square only a wisp of their haunting tunes can be heard. But nothing answers back at all - except for some street neon automatically flashing: "Merry Christmas." Stationed between the largest store in the world and the tallest building in the world, the devotees of Lord Krishna continue to try to remind the great city of gradual decline of spiritual civilization over these last five millennia.

Christmas Eve Festivities

Christmas Eve: the temple celebrates the Disappearance Day (anniversary of death) of Prabhupada's spiritual master, Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati, whose picture hangs in the temple room and stands on the altar.

A dozen devotees have been sewing new deity-clothes furiously for weeks, adding what they call "jewels" but which are in fact sequins and plastic beads to an elaborate Chinese red moire print. Though stricken with a kidney infection last night, Rukmini's last words before being rushed to the hospital were sewing instructions. To finish in time, three or four of the women stayed up all last night; consequently, they sleep right through the eight hours of morning festivities.

The Brahmins in the kitchen have been working on the Sunday feast since yesterday. Scrupulously bathed, they stand barefoot among huge vats of raw spinach and tomatoes, washing, peeling, chanting. Doors are closed against outsiders. "If all you want to do is look, don't come around the kitchen," says the tall black devotee Bhutbhavananda.

I oversleep and am yanked out of bed at 5:30 by a dismayed roommate. When I have bathed and staggered downstairs to chant, another devotee hands me a lily…

Coming through the door is an enormous hot-pink, cardboard lotus petal, almost dwarfing its human bearer. Brahma will be born from it on stage this evening.

Because it is the day before Christmas, some pine branches, colored Christmas-tree lights, and silver tinsel have been added to the always ornate temple room. Their wintry colors make a striking contrast to the rows of pink, chartreuse, saffron, and magenta sequined banners that line the ceiling moulding, the usual decor in this yellow-walled room. The Apple recording of "Govinda" is being played more often than usual today.

No one is to eat anything from awakening at 3:30 till breakfast at 1:00.

The usual morning service of offerings, singing, and chanting is supplemented today by readings from the work of Prabhupada's guru, Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati, a tape of Prabhupada talking about him, and additional offerings. Devotees execute the general temple cleanup exuberantly. Nevertheless, more people than usual doze off in the 7:00 class. Yesterday nearly the whole temple was out on all day sankirtan; few got even six hours of sleep.

Between ceremonies, the Vaikuntha (Spiritual Sky/Anxiety-less) Players dash downstairs for a last-minute rehearsal of their production of the creation of the universe.

Everywhere, devotees are carrying mops and pails, and sheetfuls of dhoti and sari laundry. Prabhupada's quarters are getting their regular twice-weekly scrub, the woodwork already totally free of any possible dust, gleaming.

The holy book Brahma-Samhita is read, with the late swami's commentary. It is unbelievably esoteric. No one understands even the English.

Prabhupada speaks through a blurry tape of his brief experience with his teacher.

Simply understanding the spiritual master's words, on the literal level, from these tapes that play in the background during every meal, is considered a good sign of adaptation to temple life.

Finally at one o'clock the devotees get their first meal of the day: generous heaps of lettuce, cucumber, and tomato salad with yoghurt dressing. In the women's room the conversation focuses piously on Prabhupada's spiritual master. Having been told by Bali Mardan that the holy man in question was an "astrophysicist," I am interested to hear the girls describe his occupation as "astrologer." I am fascinated by their tale that after Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati's death, his disciples quarreled so badly that all the money from the sale of his printing press was spent on lawsuits against each other.

("Close that! You're not supposed to be reading it! It's not written by a realized soul!" This I overhear Rukmini, the head deity-worker and a high school dropout, say vehemently to a devotee leafing through a book by an unauthorized disciple of the man being honored today.)

After this light meal, stomachs half-empty for the feast later, the devotees split for an afternoon nap. The official schedule reads: "Sri Sri Radha Govinda [the deities on the altar] take rest." There is a breathing period.

At 5:00 P.M. the devotees reassemble for the "swing festival," a regular feature on Sundays. Two hundred or more guests pile expectantly into 439 Henry Street, checking their coats and shoes at the reception desk. Many Indians arrive: groups of families of plump young adults, squalling infants, and hugely majestic grandmothers. They exude an air of belonging here, of appreciating the Hare Krishna temple because it is part of their own church-on-Sunday traditions still to be respected.

"You don't have to tell me about Krishna. I know all about Krishna!" a young Indian man says to a devotee, pulling an edge of his sacred Brahminical cord out from under his collar. "See? I have the sacred thread!"

There are Brahmins in India who object to the Hare Krishna movement's nonhereditary production of Brahmins through merit and training. But those Indians who approve of ISKCON are a potential source of support; a long list of them receives mail notification of temple events.

American guests at the Sunday Feast are mostly young blacks and white hippies. Some wear colorful, long, Oriental-style clothes. Others come in jeans and T-shirts.

In a month at the temple I saw many Indians and some hippies come regularly, almost a lay congregation. I recognized a bunch I had seen at the feet of another yogi. A group of feminists pressed me for an interview. I listened as some touchingly straightforward youngsters in cowboy-hippy clothes soaked up every proselytizing word fundamentalist preacher Jayadvaita had for them.

A sprinkling of middle-aged white men, with a tendency to squint and leer at the girls, also appear among the crowd.

When all pile in to the smallish temple room, the heavy weight of the outside world fills and thickens the air. Their body heat, sweat, and sluggishness give the "great mantra" its special, public flavor. Only a small percentage of the outsiders actually join in with the dancing and singing: in general the hippies know the words and the young blacks dance enthusiastically. The rest stand around, rather dazed by the rhythms of the ear-splitting, amplified voice, drums, and cymbals, and the extra-powerful incense. A few Indian children wander freely about the center of the floor, playing with the scattered rose petals.

Indian couples in their Sunday saris and mod shirts seem preoccupied with private concerns. Though the word karmi is used at the temple to denote all outsiders, i.e., anyone attached to the fruits of consequences of what he does, in the spirit of the holiday festivity Hari Puja says, "No karmis come to the temple. They're all devotees!"

Unusually large numbers of people participate in this Christmas Eve Sunday offering and put their fingertips gingerly on the swing that rocks Radha and Govinda back and forth. Temple devotees chant especially loudly, enunciate with special clarity. The overall atmosphere becomes oppressive. Soon arotik is finished and Jayadvaita gives a sermon.

Everyone sits down on the floor, now strewn with flower petals. The "swing" of flowers, sequins, satin, brocade, tassel, and pearl is disassembled. Eyes wander from the orange-gold curtain now hiding the altar to the pink, purple, and orange velvet throne at the other end of the room.

Jayadvaita today discusses brahmabhutam, "the platform of self-realization." The beginning of spiritual progress, he says, is the realization that "I am not this body." From this realization one becomes jolly, because the body is not jolly.

"Immediately, if you come to the temple, you don't have to wait, you don't have to practice any difficult austerities, you will have realization. Chanting, dancing, feasting, philosophy: by this simple program you will learn how to solve your problems."

The editor-preacher goes on, the audience not listening so much as mesmerized. Easy access to Krishna Consciousness is one of Jayadvaita's favorite themes.

Finally the feast is ready. Half the devotees in the temple stayed away from the swing ceremony in order to pitch in on a huge assembly line in the basement dishing out tubs of food and carrying trays of it up the stairs, where it is now being served on individual plates from the floor.

Fatigued guests stream in, delighted by the delicacies. A few devotees stealthily pick up two or even three plates for their own consumption. Audacious children skim off their favored items from several plates. Typically, the feast contains such Indian delectations as bharats (spicy lentil pastry), ladoo (sweet balls of seeds, honey, and nuts), puri (deep fried bread), firni (sweet rice pudding), ras gullah (cream cheese curd ball), halavah (farina candy), home-made potato chips, and one or two unique vegetable combinations. In addition, there are rice and chuppatties, and lemonade to drink.

The guests crowd the art gallery and men's dining room. When they have taken paper plates and seated themselves, there is not an empty spot left on the floor. Eating, they talk excitedly among themselves and to devotees on philosophical matters related to Krishna Consciousness. Some devotees enjoy this form of discourse; but many more are hidden away from the guests entirely, in rooms by themselves.

In an hour, the food has disappeared, the paper plates are discarded.

The art gallery darkens. If you have not already found a good seat, it is too late. Both doorways are packed with guests and devotees straining to see the stage. The curtain is about to rise.

On the Sunday of the Disappearance of Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati, the theme of the play is the creation of the universe. Ananda Baram, compiler of these productions for the New York temple, says a few words of introduction.

Vaikanas plays jazz flute, unseen behind the curtain. Melodious Sanskrit verses are heard.

Lord Brahma, the first spiritual master, supreme in the universe, could not trace out the source of his lotus seat, and while thinking of creating the material world, he could not understand the proper direction for such creative work, nor could he find out the process for such creation.

The curtain goes up, revealing an unearthly shimmering light, and evocation of the dawn of creation. Seated on the big pink cardboard lotus is the devotee Bharadvaja, now transformed by a long black wig, jewelry, and silk into Lord Brahma. He is looking around him, as perplexed as only the supreme entity in the universe can be.

But direction is to come.

From the Chintamoni (Touchstone) verses of the Brahma-Samhita, we learn that Brahma-ji,

while thus engaged in thinking, in the water, heard twice from nearby two syllables joined together. When he heard the sound, he tried to find out the speaker, searching on all sides. But when he was unable to find anyone besides himself, he thought it wise to sit down on his lotus seat firmly and give his attention to the execution of penance, as he was instructed.

Somehow the Hare Krishna devotee-actor-Brahma manages to suggest the vastness of the beginning of time. The audience shudders.

The actor-Brahma then engages in chanting a mantra, which we are told he continues for a thousand years. At the end of this time the devotee and karmi audience, for whom only a few minutes have passed, are presented with the second major tableau of the evening.

Woodwind and Sanskrit intermingle:

The Personality of Godhead, being thus very much satisfied with the penance of Lord Brahma, was pleased to manifest his personal abode, Vaikuntha, the supreme planet above all others.

At these words the most beautiful woman in the temple emerges from the wings, suggesting by her movements and the gestures of her hands "the transcendental abode, adored by all self-realized persons."

More scenes follow. Our universe is created. Brahma takes a human form there.

But my own attention departs. I recall the first time I saw the devotee-actress Susan. She played Krishna, her face and arms dusted blue. Her costume was magnificent, like the clothes on the altar deities. The makeup and jewelry on her moving face, as she imitated the flashing of Krishna's eyes, were stunning. She assumed the pose of playing-the-flute. Her hands spoke. And when the devotees fluttered long strips of grey chiffon before blue and green lights, the stage was enveloped in storm: it was India, five thousand years ago. As the devotee-actress-Krishna casually lifted a mountain with a finger, appearing to float six inches off the ground, I could not convince myself I was looking at a human being. Susan was Krishna.

Later, when I met the woman and learned it was she and not Krishna Himself who had been on stage, I was almost disappointed. She accepted my compliments modestly, saying appropriate things about it really being Krishna. It was clear her heart was in the dance…

Many of the devotees in tonight's production were also part of the erstwhile Hare Krishna "road show." Some even joined the movement just to participate in that show. For several months in 1972, a band of Hare Krishna players made a circuit of college audiences performing a Vedic musical comedy.

But all that was ended abruptly by Prabhupada, ostensibly because he disapproved of devotees dressing up in karmi clothes and felt that no such "gimmickry" was needed to spread the Hare Krishna message..."

Excerpt from

The Strange World of the Hare Krishnas

By Faye Levine

Copyright 1974